|

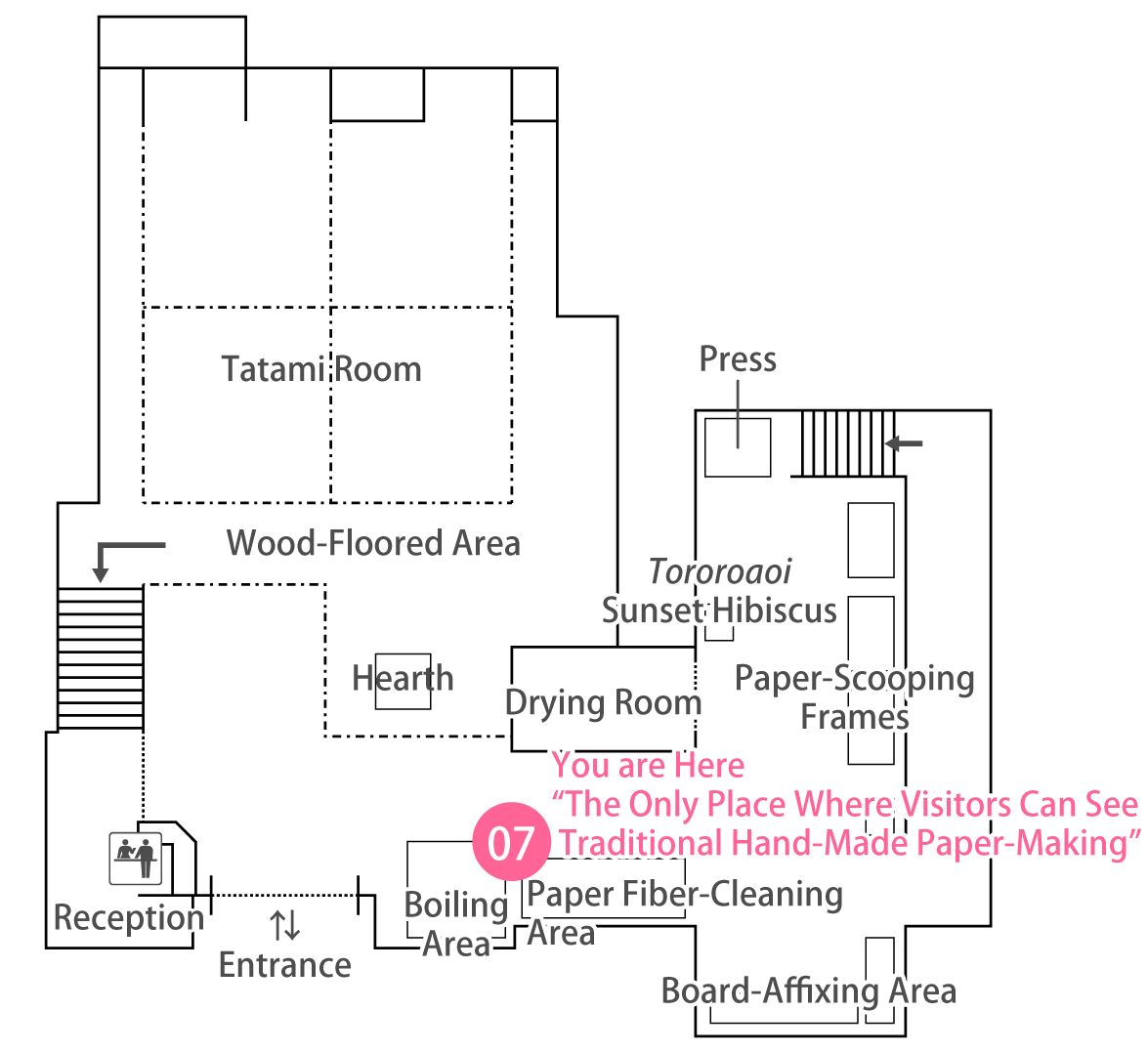

[07] Washi Paper Workshop |

The Only Place Where Visitors Can See Traditional Hand-Made Paper-Making |

Washi paper is stronger than western paper, yet made of natural materials, giving it a distinctive resilience, even to humidity, allowing some pieces of washi paper to have survived for over a thousand years.

To continue making high-quality paper with the characteristic sturdiness of the plant fibers it's made from, Echizen washi paper masters have worked to improve the techniques of hand-making paper.

|

If you travel from the wood-floored area to the washi paper workshop, you can see the traditional equipment and tools of every step of paper-making, from making the raw materials to forming the paper to drying it, and watch as the paper-making masters show and explain the process, step by step.

If you have any questions during the explanation, feel free to ask; the paper-making master will answer to the best of their ability, and would love to be of assistance for everyone's questions or requests.

|

| Floor Map |

|

Ingredients of Washi Paper |

|

In the Boiling Area, plants that will become the raw materials of paper are boiled to process them for use. A number of different plants are used, depending on the intended use or finish of the paper. Here, we will talk about a few of the most common types used for making washi paper.

|

| Paper Mulberry |

|

|

Washi paper production began with paper mulberry as its main ingredient, and its strength lends itself to its use for paper-covered sliding doors, official documents, paintings, and calligraphy, among other uses. Because of its ease of cultivation, paper mulberry is grown nationwide, making it the most popular material for washi paper. With its 15–20 millimeter-long fibers, paper mulberry produces paper that is strong, beautiful, and flexible.

|

| Gampi Shrub |

|

Paper made from the gampi shrub is resistant to damage from insects, and its durability makes it a popular choice for printing, etching, Japanese-style paintings, copying sutras, and other tasks.

Gampi, with fibers 4–5 millimeters long, is often mixed with paper mulberry for paper-making, and produces paper that resists insect damage, is durable, and has a smooth surface for ease of writing. |

| Mitsumata Paper Bush |

|

|

Paper made from the mitsumata paper bush is thin and absorbent, making it perfect for banknotes, printing, etching, postcards, books, and more. It produces paper with an exceptionally smooth surface, and its absorbency gives it a rich luster.

|

The paper-making process involves breaking up the plant fibers in a large tub filled with water, then the critical step of properly scooping them up into a mold. In addition to this step, master paper makers have refined their knowledge and technique over the years in the steps before and after these, as well.

These processes result in the production of the highest quality paper available in Japan.

|

| Washing the Paper Mulberry |

|

|

Ordinarily, in front of paper-makers' houses, there would be a river or irrigation stream, and they would leave the raw plant materials in the water overnight to soak and clean.

This process would make the materials softer and easier to cook down, and would wash out any particulate impurities like sand or litter, as well as starches, oils, or tannins from the plant bark that would cause the finished paper not to be an even white color.

|

| Cooking Down the Bark |

|

|

In the boiling area, the bark of paper mulberry, mitsumata paper bush, and gampi shrub are boiled in a solution of lye and plant charcoal to produce the cellulose necessary for making paper. By thoroughly boiling the bark, the plant fibers come unbundled, and at the same time, substances in the bark that would be bad for paper, like lignin, are dissolved into the solution, allowing for even, beautiful paper to be produced. |

| Paper Fiber Cleaning |

|

In the paper fiber-cleaning area, impurities in the boiled bark, as well as things like scarred bark or seedlings that would show up in the finished paper are carefully removed. This work requires patience and attention to detail. One or two pieces of bark are floated in the water and gradually spread open with the fingertips to remove any unwanted materials, working carefully all the way to the tip of each piece.

This process of cleaning the paper fibers is crucial for making high-quality washi paper, and is sometimes repeated two or even three times for particularly thorough cleaning.

|

| Beating the Cooked Bark |

|

After cooking and bleaching the bark, the plant fibers are bunched together and tangled up, so the mass of plant fibers is beaten to untangle them, making them finer and more pliable. Thoroughly beating the plant fibers also renders the final paper more resistant against ripping and more durable when folded. There is a delicate balance at play: beating the plant fibers too much can cause the fibers to weaken, while if the fibers aren't beaten enough, then they will be coarse and produce brittle paper.

This vital process requires thorough knowledge of the materials and plenty of experience and technique on the part of the paper maker, to know just how much to beat each different kind of paper-making plant fibers.

|

| Paper-Stirring |

|

|

After the cooked plant fibers are beaten, they are placed into a bag and thoroughly stirred to wash out any starches and other impurities, making for a whiter, stronger finished paper.

|

| What is "Tororo-aoi" Sunset Hibiscus? |

|

Sunset hibiscus is a plant that is used to make the adhesive that sticks together the fibers of the plants used to make paper.

Crushing the root and steeping it in water will cause the root to release a thickener into the water. This liquid is then put into a bag and filtered to remove any particles, and is then poured into the tub along with the plant fibers being used to make paper.

Even today, only natural materials are used in this process, producing paper that can survive for a thousand years.

|

| Paper-Mixing |

|

Before forming the paper itself, the plant fibers and adhesive thickener are carefully mixed together in the tub.

Depending on what plant the paper is made from, or depending on its intended use, the balance of fiber and adhesive thickener has to be carefully adjusted; this critical step marks the beginning of the paper-forming process.

|

| Tools Used for Paper-Forming |

|

Suki-bune tub

The large tub used to mix together the ingredients for making paper.

|

Suki-keta frame

A frame used to form paper along with the suki-su mat. The assembled suki-keta frame and suki-su mat is known as the su-geta.

|

|

Suki-su mat

After scooping paper fibers and adhesive out of the suki-bune tub, the paper is formed on top of this mat. Most of these mats are made from thin rods of whittled bamboo, bound together with silk or horsehair.

|

| Paper-Forming |

|

|

Finally, the paper is formed in the nagashi-suki style in this step. The paper frame is repeatedly emptied and refilled to ensure that just the right amount of material remains in the sugeta frame.

Experienced paper-making masters use this process to carefully produce paper that is thick yet flexible, or paper that is thin yet strong, sheet after sheet, all with identically high quality.

The formed paper is then stacked together.

|

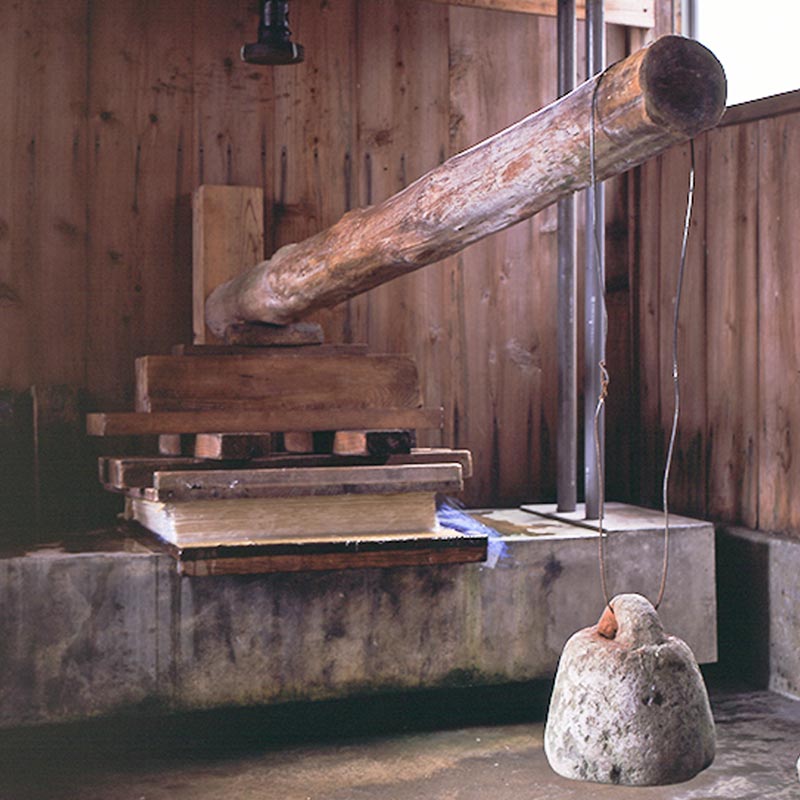

| Paper-Pressing |

|

|

|

The stacked paper is then pressed to remove the water still in it. The process of pressing the water out of the paper is fairly simple, but care is still necessary to prevent the paper from becoming misshapen as pressure is applied. |

| Spreading and Drying the Paper |

|

|

|

After it's pressed, the still-damp paper is spread and laid out one sheet at a time on drying boards, using a roller to attach it. The drying boards are made from female ginkgo trees, carved smooth, and are used to carefully check the paper to see if it's good or not. The process of sun-drying paper on drying boards has become fairly rare nowadays, with drying rooms becoming much more common. |

Authentic Hands-On Course Information |

|

We offer a course in making washi paper in the nagashi-suki style, using genuine traditional tools and materials, taught by a METI-designated traditional craftsperson. Including instructions and practice time, the course takes over an hour.

|

If you're interested in participating in our hands-on course, please contact the Udatsu Paper & Craft Museum.

Same-day reservations are available, but there is a possibility that we will be unable to accommodate same-day reservations based on requested time, number of visitors to the museum, or other conditions pertaining to the museum.

Same-day reservations are not available for groups of five or more participants; please email the Udatsu Paper & Craft Museum at least two weeks ahead of time to make a reservation.

Additionally, we do not offer hands-on courses for other paper makers.

Email address: udatsu@echizenwashi.jp

|

Fee: ¥5,000 per participant (does not include shipping fees*)

*Paper made in the course will usually take two or three days to fully dry. Once it is dried and finished, it will be shipped. Paper can be sent to the participant's hotel in Japan or directly to their home overseas, as well; feel free to discuss this with us. For groups of five or more participants, the finished paper will be sent in a single shipment to a selected member of the group.

|

|